OpenAI just released GPT-5 yesterday, and I’m just now trying it out as of last night. While I’m glad that I won’t have to keep trying to figure out what the differences are between 4o, o4, 4.1, 03, o4-mini, and o4-mini-high, it seems that OpenAI is letting GPT-5 choose which version of the model actually does the work without telling the user. This, obviously, could further erode replicability:

It could also explain why the model sometimes has trouble counting the number of B’s in “blueberry” - is it GPT-5 answering, or is it GPT-5’s less intelligent cousin who picked up the phone this time? There has to be a better way of getting AI to do a good job consistently than having to tell it to “think hard.” For these tools to be transformative in high-risk business applications (like law), we can’t keep invoking them with magic spells, or feeling like we’re repeating my second-favorite line from The Holy Grail:

Yes, GPT-5 is impressive, but there’s got to be a better method for the end user.

Speaking of magic:

One of the more magic-seeming use cases for generative AI is the seemingly effortless ability to create little educational games. Don’t take it from me, this is actually one of the promoted use cases that the OpenAI people showed off in the launch announcement yesterday (this should start around the 17:30 mark):

Last night I did have GPT-5 create a little quiz game in React about the Federal Rules of Evidence, just for fun.

I think we should pause and distinguish here between vibe-coding single webpage games in react like this guy shows off, vs. coding a full-stack business-class application with persistent storage and integrations with other applications. No, these little apps aren’t production ready right out of the box. There’s probably not a real business case for creating these and then selling access to them under something like a SAAS model, especially when any potential customer can just go to ChatGPT or Gemini and make their own based on their own preferences.

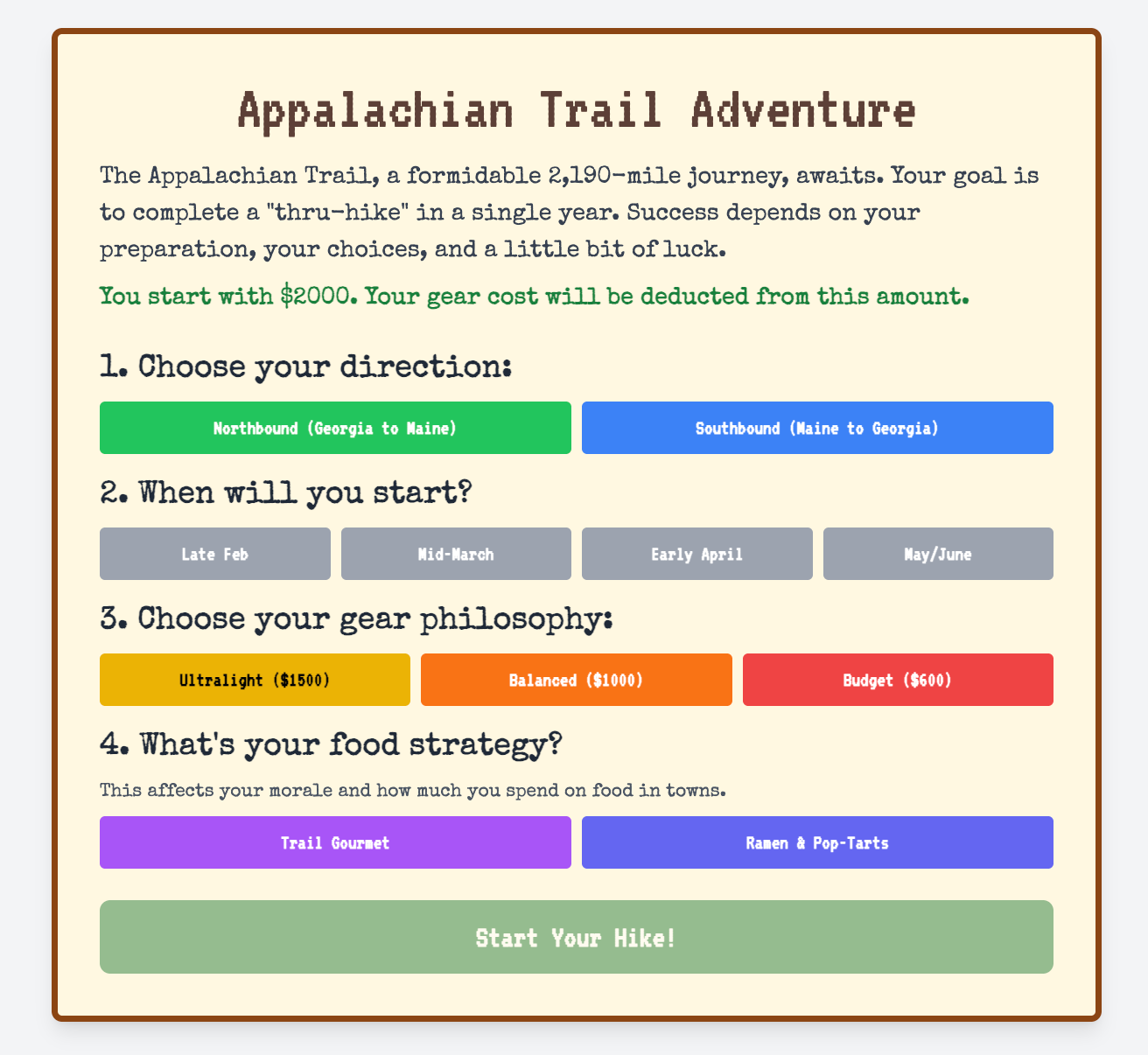

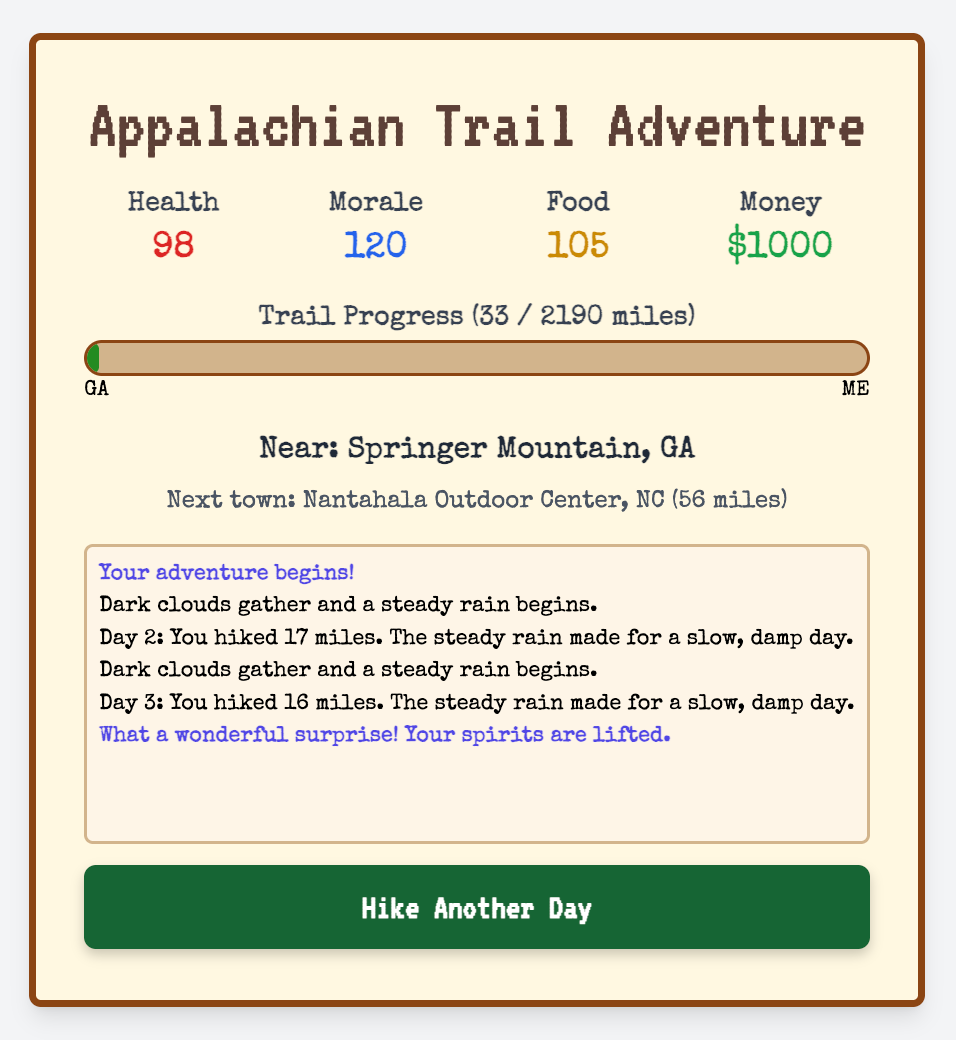

But are those the only value propositions here? I got to thinking about the Oregon Trail game, which, if you’re of a certain age and came through the American education system, you’ll instantly remember. It’s not hard to recreate an Oregon Trail look and feel via vibe-coding without even mentioning it. Here’s an “Appalachian Trail Adventure” game Gemini created for me that’s very Oregon Trail-ish, minus the hunting wild game part (it’s probably frowned upon on the trail). But it’s actually pretty cool - you get to choose your options which end up affecting your gameplay:

I’ve found the best way to create this kind of stuff is not trying to one-shot it with a hugely complicated prompt that starts out with “You are an experienced developer who is proficient in creating browser-based javascript games…” Rather I find it to be like sculpting the elephant from a large block of marble - start small and just keep chipping away till it looks like what you want. Here’s the entire discussion with Gemini 2.5 if you want to see it (my side only, complete with typos, and I now realize much I use the phrase “Ok great”). My point here is that if you want to make something with these reasoning tools, you have to kind of treat them as an “alien intelligence” like Ethan Mollick is fond of saying. I’m not saying you need to beg, threaten, or flatter them either - just have a discussion where you articulate your goals up front, and then make change requests to chip away till you get your elephant. It’s like a combination of two very different concepts: the dialectic method of learning, and the idea of Kaizen (continuous improvement). And while it’s tempting I’m not going to try and create some awful portmanteau from those two words.1

Value:

Back to value. I was in elementary school in the mid-1980’s, and vividly remember playing the Oregon Trail game on our Apple computers in the lab on the third floor. But until recently, I didn’t know that the original Oregon Trail game was about a decade older, and was written before GUI’s were a real thing - it used a teleprinter! The original one was written over about two weeks by three guys in college (the idea guy was Don Rawitsch, a student history teacher), as a tool for teaching elementary school students about history. None of them made any actual money from it, and you probably had no idea who the original developers really were.

But what a thing of value they created. If you have some time go and read the AMA with Don Rawitsch on Reddit from about a decade ago, and see how many people say things like “Thank you for setting my life's course.” Or watch this presentation he did for the “Dust or Magic” conference nearly 15 years ago:

Games are effective AI demonstrators, I think, because they combine creative visual elements as well as reasoning about mathematical, logical, and textual elements. I’m not saying here that my little vibe-coded Appalachian trail game, or the OpenAI guy’s french tutoring game, would ever be any where in the same universe of value as Oregon Trail. But what a powerful way we have now to experiment quickly, and see what does and does not create value.

What could vibe-coded games possibly have to do with legal?

Think about the tasks that law firms, legal aid organizations, and legal departments do on a daily and case by case basis. A lot of the “Legal AI” tools exist to solve a problem in one conceptual task - contract analysis, billing, legal research, matter management, and so forth. To create a even a semi-complex game, you have to bring in concepts and tasks from across the concept spectrum, be they math, logic, text, economics, graphical elements, character development, or word play, and mesh those into a cohesive whole with understandable themes and end goals that the player works towards. Moreover, games require a certain degree of creativity, whatever that means to an AI. In Legal AI, we tend to still think in discreet tasks and silos, such as:

summarize this one document into key points,

create a list of potential witnesses from this deposition,

identify counter-arguments to this memorandum of law.

Law, and law practice, are multifaceted across many different areas. Discreet analytical tasks are a part of it, but law encompasses a lot more. Imagine something akin to my interaction with Gemini 2.5 which created that little game, but in a medical malpractice matter:

We just got a new file from Client XYZ - can you go through it and give me the run-down as well as recommended next steps? Include the usual fee agreement and engagement letter, and also get started on the medical records requests we need.

It looks like the adjuster had set the initial value on this to a range of $Xish - which is lower than your valuation. Can you flesh that out a bit more for me on why that is? And get me a memo on a motion to dismiss on this, just to cover the bases.

I’d like to get some requests for admissions about previous treatments and comorbidities this guy had, add those in to the initial discovery.

You can remove that affirmative defense about jurisdiction, otherwise they’re fine, will take a look again later.

Ok great - will you flesh out that section in the letter to the client about the co-defendants? And schedule a call for me in a week or two with Jane Scantron about her client Dr. Ganon, but get me recommendations on the upsides and downsides of a joint defense agreement first so I can send it to our client.

Granted it’s been a while since I was involved in a med-mal case, but hopefully you’re getting the picture. Instead of siloed tasks where the prompt is a five-paragraph essay with stage direction, we could soon have a world where the lawyer and the AI are having a back-and-forth discussion over the self-directed actions the AI is taking on a client matter. It’s not e-filing things on its own, or sending client communications, but it’s able to have a view of different systems and connect the dots between them, take actions, and decide on paths to take. The attorney is able to watch the steps in the journey take place, redirect, and make course corrections as necessary.

That’s a very long way of saying that I think the discreet task era of Legal AI could be ending soon. To do this, we need to think a bit like game designers, a bit like history teachers, and maybe a just a little bit like magicians.

Dialectikaizen doesn’t really roll off the tongue, let’s be honest.