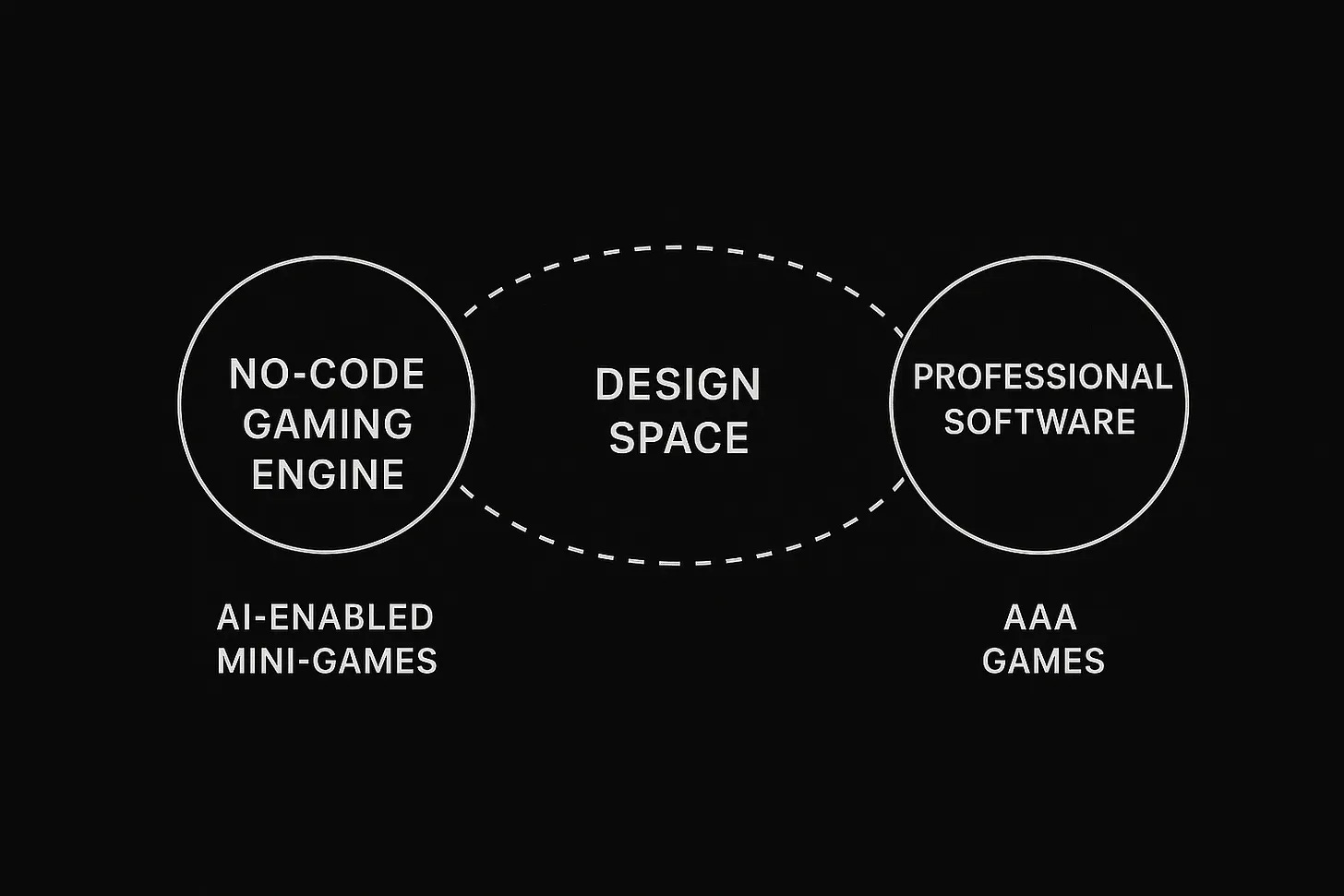

There’s an article about AI and video game development that someone turned me onto, and it really got me thinking about things. The image above encapsulates the central theme - that real innovation is going to happen somewhere between two extremes: free experiments on one side, and industrial-strength AI features on the other. Here’s a good excerpt:

Today, AI-enabled gaming teeters intriguingly between experimental promise and practical reality. Platforms like Rosebud.ai showcase how mini-games can be rapidly crafted with AI’s assistance, resulting in low-cost productions that, while high in creative variance, typically face steep user retention challenges and distinct power-law dynamics.

On the other side of the spectrum are games crafted meticulously using traditional tools like Blender or Unreal Engine, which embody AAA production readiness, are richly immersive, yet demand significant expertise and technical investments.

The true creative frontier lies in the liminal space between, marrying the speed and flexibility of generative production with experiences people want to revisit, linger in, and hold close. This middle ground is misty, unmapped, an expanse of questions and untapped forms.

from the FakePixels Substack post “Infinite Playgrounds.”

Even if you’re aren’t remotely into video games, I’d recommend reading - it’s fascinating stuff. And if you doubt AI’s potential to actually do things, take a look at the games on Rosebud.ai. There’s some wild stuff there that’s just vibe-coded. There’s also stuff like this:

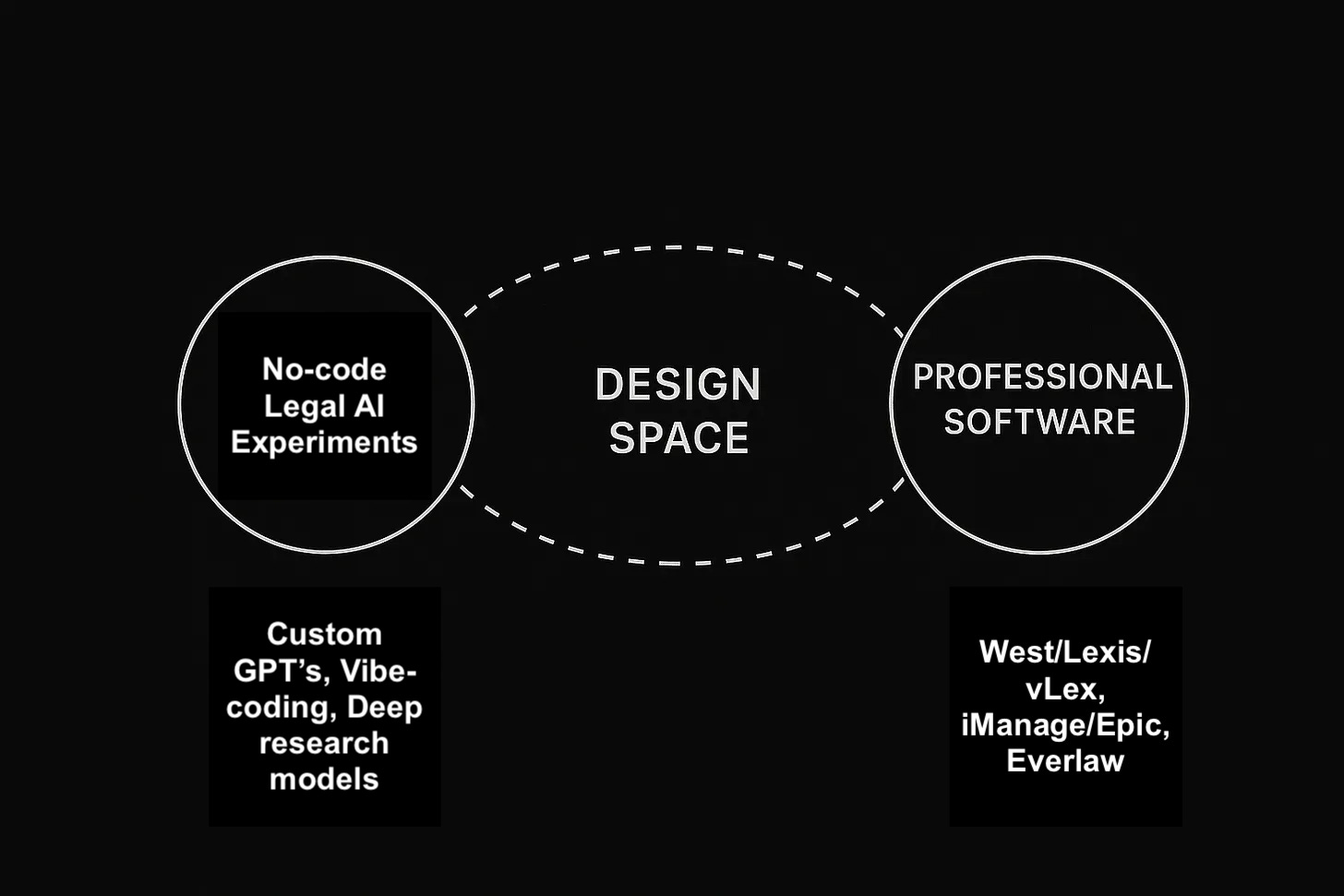

Anyway, I’ve been thinking about legal AI a lot, and how the creative frontier might similarly exist between two extremes:

I think the most potential lies somewhere between the world of vibe-coding, concierge chatbots, and deep research-generated legal memos, and the industrial-grade world of the legal research, document management, and e-discovery giants. That’s not to say that there isn’t creativity involved on the experimentation side, or that it’s unnecessary. Rather, experimentation is a very important part of actual innovation, yet we’re seeing a lot of experimentation without meaningful customer feedback and input (a lot done by me). I firmly believe experimentation - even experimentation in public - is necessary in this space. But a lot of the no-code stuff is either inside a walled garden (like custom GPT’s on ChatGPT) or the outputs are simply too hard for the experimenter to fuse together into something that’s marketable.

I don’t really see creativity coming from the professional software side these days. Instead, they all seem to focused on customer retention and solving that pesky hallucination problem rather than doing anything truly novel. Enterprise software will, I think, start to move away from relying on users to prompt for the correct outputs and instead put their users on rails to accomplish a set of pre-defined tasks. Something like a button-initiated workflow to summarize a deposition, maybe with choices on topic areas to focus on. Not that there’s anything wrong with that - but it’s essentially just enhancing existing workflows and not new.

I think the middle is where the really interesting use cases will be, and where the innovation will happen. True to form, I came up with a couple of examples of what I think this might look like, and here they are:

Adaptive legal coaching that’s context aware:

Right now we see AI being used at discreet points in time for addressing legal needs. People use ChatGPT to give them advice about their situation as it is right now, and if their situation changes, they have to go back an input the same info plus what’s new. Instead imagine a “legal coach” that’s essentially wired up to receive current information about the user’s matter, either through a court system feed or one through their law firm as it happens, and is able to affirmatively give the user information. So the AI legal coach would receive the notice about an upcoming court date in the user’s DUI case, notify them about it, put it on their calendar, and suggest that the user review what’s happening, the current offer from the prosecutor, and what their options are.

Now imagine that this experience could use an interface like Google’s new AI-enabled eyeglasses.

Estate planning from beyond:

Currently we have three ways1 of declaring what happens to our stuff after we shuffle off this mortal coil:

Don’t make a will and let the court sort it out according to the laws of probate;

Make a will and hope that the administrator of the estate is able to find it and actually follows it; and

Create a trust and empower the trustee to make some limited decisions.

This is going to sound sci-fi, but imagine if, instead, we could create AI Trustees-as-Agents that are like mirror copies of our intentions, and let those make the decisions for us after we’re dead. So instead of a will, a person would contract with an AfterlifeAI Agent provider that creates the agent, trains it to your thinking patterns, and validates it. When you die, the agent takes over control of your assets and decides what to do with your ungrateful and and, frankly, undeserving heirs. No matter how your ne’er-do-well grandson Timmy tries to prompt-inject his way to getting his inheritance, your AfterlifeAI Agent stays the course. Stay in college, Timmy!

Lawyer as AI-wrangler:

I think most law firms still see AI as some sort of workflow enhancer, like a tool that can speed up the number of already-existing discreet lawyerly tasks lawyers do on a daily or weekly basis, and then work out some way to bill for those tasks. I don’t know of any firms who are taking the time to actually re-think their workflows in light of traditionally time-bound tasks being essentially unconstrained by time, but by compute.

An example: let’s say a firm bills 5-6 hours of time to have an associate write out an initial liability analysis after a medical malpractice action is filed, have the partner review it, and send it to the hospital’s insurance adjuster. Considering that, in theory, a deep research model can do this in minutes for a negligible amount of compute, does that task remain a valuable one? The purpose of these initial liability assessments, which are typically based on the allegations, the medical records, and the type of damages sought, is to see what value the insurer should place on the claim in anticipation of settlement negotiations. What if the insurance adjuster receiving it simply asks their own AI to summarize the key points for them and never actually reads it line-by-line? Is creating such a liability analysis and report still valuable? I think the question we should ask is not “is this a valuable a task to automate”, rather “is this a valuable task at all”?

Companies used to pay tens of thousands of dollars for a single research report, now they can generate hundreds of those for free. What does that allow your analysts and managers to do? If hundreds of reports aren’t useful, then what was the point of research reports?

From One Useful Thing

What if a law firm got together with its clients and tried to hash out where, in this strange new world we live in, it actually provides value to them? It’s easy to measure value through deliverables, like reports, documents, and such. It’s harder to measure value through downstream effect.

Lawyers are, by and large, the most expensive cogs in the litigation machine. Law firms know this, so they stuff the machine full of lawyers (or “billing units”). Law firms, could, in consultation with their clients, experiment with the idea of a lawyer not as a billing unit, but as the leader of a team of AI agents that chew through legal tasks and analyses, and evaluates the outputs to determine the path forward. The lawyer’s value proposition is not simply billing time or producing work product, but in acting like a construction foreman: reviewing work, ensuring completeness, keeping things on track.

The middle market:

I think there’s an interesting case to be made for using AI in the normal person consumer legal market. For one, normies don’t typically hire lawyers to do things like review a contract, negotiate a lease for their small business, etc. And AI is busily chewing into the discreet tasks that lawyers have ignored:

If we think about the normie legal market, I think we have to start thinking about it as a market for advice, not legal advice per se. In the video above, is MS giving the person legal advice? Maybe? But I would guarantee that the person doesn’t think of it that way - it’s just advice, or even just a better explanation of something complicated. Maybe this idea should be in a longer post on its own, but I have thought for a long time that trying to say “people don’t see legal problems as legal problems” isn’t going to get anyone anywhere useful. If almost everything is a legal problem (or is rooted in a legal problem), and the only solution is to use a lawyer, society will effectively grind to a halt.

But I think AI is going to eat into that space pretty quickly, and the lawyers who will see that as a market might be successful if they stop branding things as legal services and come up with a better idea.

Feature or Medium

From Infinite Playgrounds:

If you think of AI as a new rendering pipeline or a clever feature, you’ll likely end up with forgettable commodities. But if you approach AI as a medium, one with its own logic, affordances, and consequences, you open the door to worlds where surprise, adaptation, and reflection are inseparable from play itself.

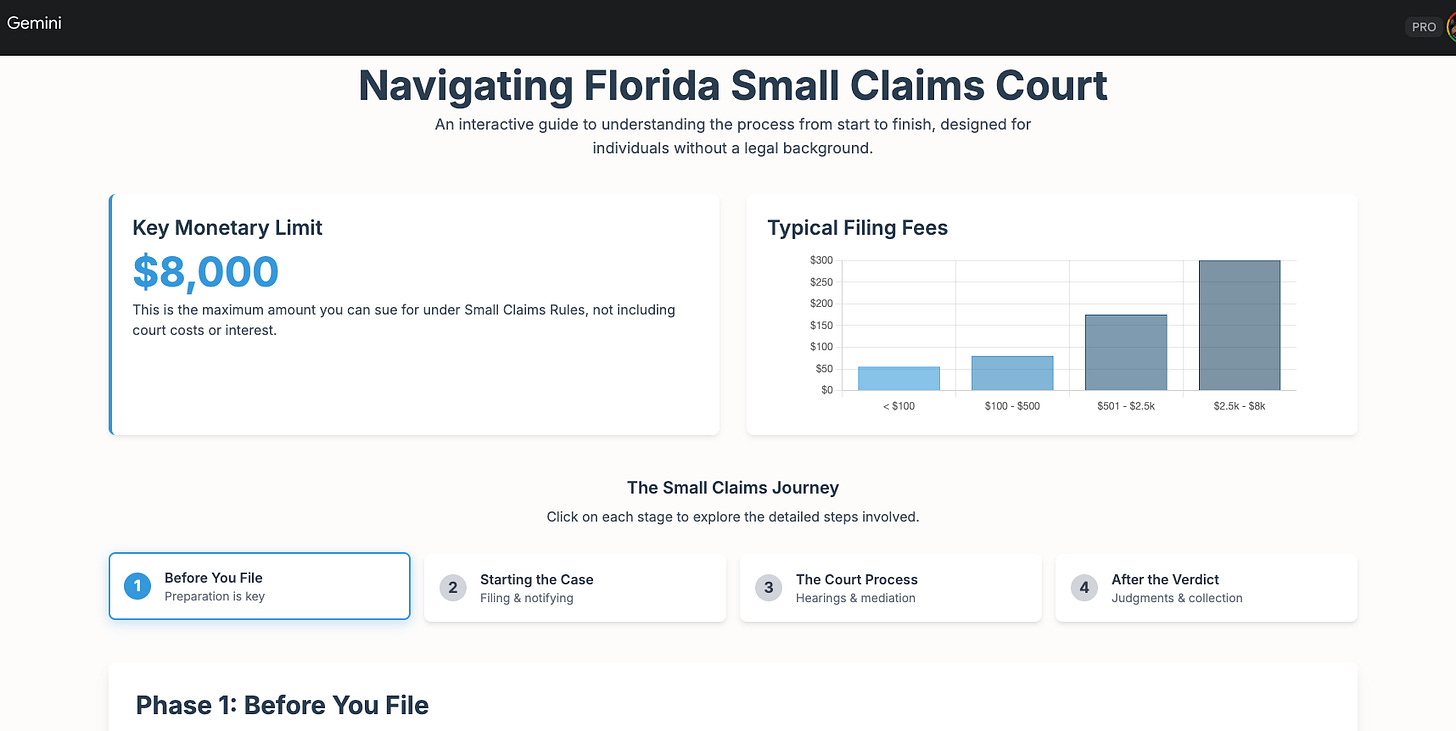

I keep wondering if the strategy of AI-as-a-neat-feature is actually going to be an advantage, especially when we see things like Gemini Deep Research’s ability to take a legal question, create a detailed explainer about it complete with sources, and then, with one or two clicks, make that into a multi-featured website with menus, graphs, and multiple pages. Or create a podcast, or …. What freaks me out / thrills me the most is AI’s ability to do nearly as good a job as humans on stuff that takes months to build and costs tens of thousands of dollars.

An example of a Small Claims Court explainer website that’s entirely vibe-coded:

Or using the live video feature help someone fill out a court form:

(I didn’t realize there was a can light reflecting into the camera like the Eye of Sauron).

No, none of this is perfect. Neither is the stuff done by humans. But I worry we’re limiting what we can be doing by not exploring that new middle ground.

At least that I remember from my Wills & Trusts class almost 20 years ago

this is a great take- the middle ground is also where the vast majority of Americans live- middle income, middle class, middle management, etc. If AI is nearly at the level of a human, why not use it creatively to address this huge gap?