There’s a conflict, I think, between two different visions for AI in access-to-justice. Let’s call them institution-centric and person-centric:

In the institution-centric model, AI enables legal aid to serve more people, kind of like adding a supercharger to a car. Legal aid keeps on doing what they’ve been doing, but simply crunches through more clients / cases / matters / legal questions than before.

In the person-centric model, AI enables people to solve their legal issues on their own, with or without help from a lawyer. This model bypasses the institution in favor of the individual, kind of like in my favorite TikTok video which seems to no longer exist, so thanks for that Joe / Don / Whoever’s in charge now.

An idea - maybe we can have both? But to do this, we’d need to start thinking about legal aid in a different way.

A lot of the AI Won’t Really Replacing Lawyers talk has been about how AI could instead allow lawyers to operate “at the top of their license,” at least in the private sector. I haven’t heard this kind of talk for the public sector / legal aid lawyers (which doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist, I just haven’t heard it).

Flaming Hot Take here, but a lot of the legal work that we load onto legal aids & public sector lawyers is repetitive. Yes, each case is unique and of great import to each client, but a public defender knows that, in general, petty theft is petty theft is petty theft. A legal aid attorney who practices housing law can probably tell you that eviction cases have very similar fact patterns, with similar landlords, and similar legal arguments.

Please understand that I’m not in any way saying that the lawyers who work in legal aid are only capable of doing low-level work. I think it’s the opposite: we have smart lawyers that we underpay and make do repetitive cases because we’re incapable of allowing something different. We don’t want Someone Other Than A Lawyer (SOTAL - my term I just coined, but use it if you want) to help someone with a routine low-level legal issue. To overuse my podiatry example, this is akin to making someone go to a podiatrist to buy insoles for their shoes, instead of just letting Dr. Scholl’s sell them at CVS or on Amazon.

What if we had some way of letting the legal equivalent of Dr. Scholl’s handle the shoe insoles, and let the licensed podiatrists handle the broken foot metatarsal-toes or whatever those foot bones are called? This also segues nicely with the idea that legal aid deserves high-quality e-discovery and AI tools, because now they’d have the reasons to use them.

The necessary corollary here is that, if legal aid and public defenders have access to the weapons-grade AI tools, we also need to let the public have access to the non-weapons-grade stuff. Another medical example: only medical professionals should have access to MRI machines, radioactive medicine, and the surgery lasers, because, well, they’re dangerous. But we (the non-medical professionals) should be able to use things like this contraption to determine which shoe inserts to buy without having to go to a doctor:

In theory, telling someone what shoe inserts they need, based on whatever it is that this machine does, could be medical advice, right?1 And yet you can still use it. But any attempt to have this kind of thing in legal (TIKD, Norman Dacey, etc.) gets met with lawsuits and lawyers talking about how the sky is falling and concern-trolling about consumer harm.

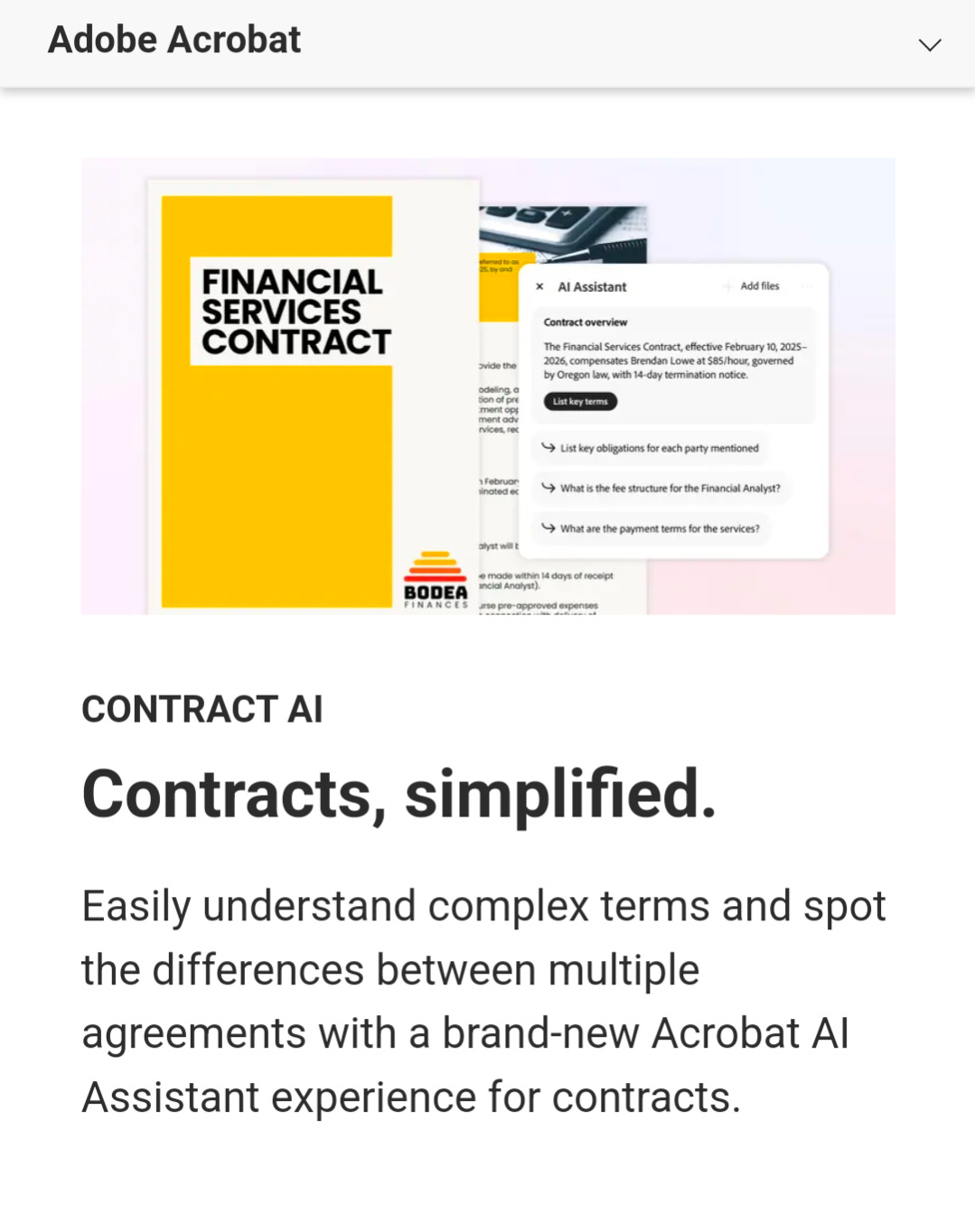

Another thing I think is happening is that, because AI is working its way slowly and quickly into a lot of the products that we already use, we’re going to see more things like this, from Adobe:

Is this … replacing lawyers? Maybe the people who would use this weren’t going to hire lawyers anyway, but at a minimum it’s replacing what lawyers say we do.

5% seems … low?

This quote from an article about how real estate agents are still finding ways to extract their 5% commissions even after the court settlement that says they aren’t supposed to made me chuckle:

Many agents say that since the settlement, they’ve felt cornered by buyers and sellers alike to defend their value. Jeremy Larsen, a Realtor in Dallas, said that consumers who decide to navigate the home market without an agent are taking huge risks with their money.

“It’s like walking into a courtroom without an attorney. Why would you do that? There’s so many possible things that can go wrong,” he said.

(Laughs in access-to-justice). But seriously - 5% seems really low compared to the 40% contingency fee that plaintiff’s lawyers charge their clients.

Unlicensed Practice of Podiatry sounds like a Seinfeld bit.